“Closer Each Day: The Architecture of Everyday Death” is a speculative work of architectural inquiry developed at Princeton University and further developed through the commissioned drawing, “Closer Each Day: Protocols for Processing,” by the Canadian Center for Architecture. The project elaborates a network of ceremonial and technological protocols to instrumentalize death as a pragmatic tool for city-building.

Decades of technological progress have distanced the material business of death from everyday life. Sanitization, disease-control, and the impulse for hygiene have kept it neat and tidy, and out of site. As a result, the contemporary city, across continents and cultures, has obviated many of the urban typologies that once played host to the social activities surrounding death.

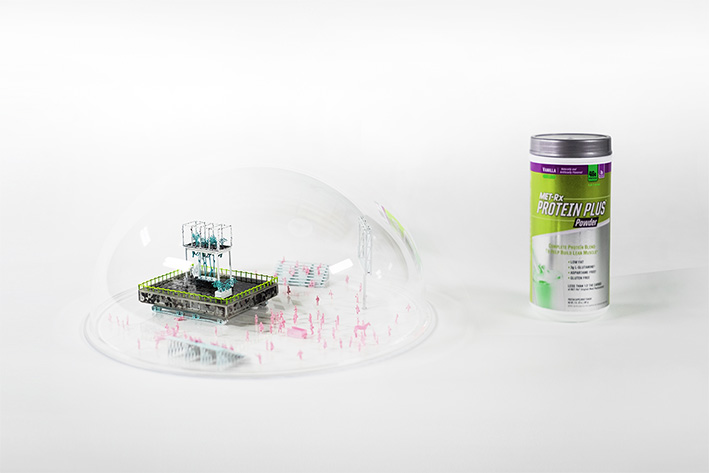

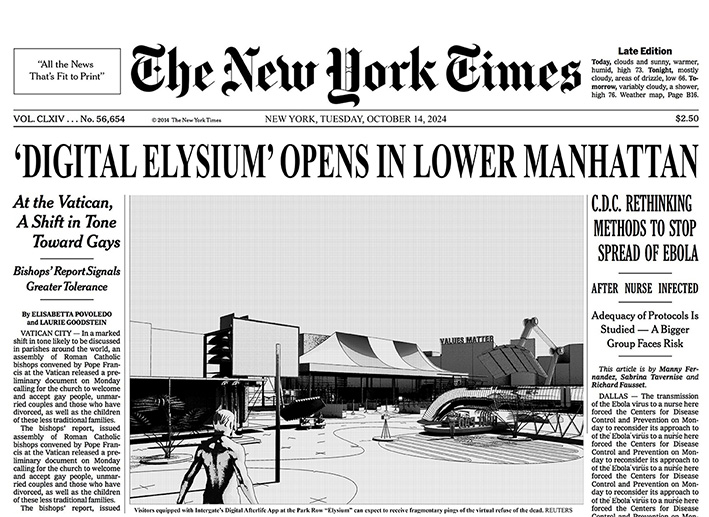

Still, death is visible in home decor, in fitness programs, and in virtual space, yet architecture has failed to acknowledge the potential posed by the latent social situations and infrastructural networks around death, and failed to recognize these entities as a site for action. Further, cities can no longer afford to keep the material business of death at arm’s length. New technologies present unique opportunities for the production of value—material, ceremonial, social, and ecological—that ought not be ignored, while traditional means of human disposition are threatened by diminishing land availability, environmental concerns, and the prospect of a digital afterlife.

One might in fact argue that today, the urban ecosystem has made sites in which death is present more ubiquitous yet less evident, and this atomization presents opportunities for death’s re-integration into everyday life. For new technologies: new traditions.

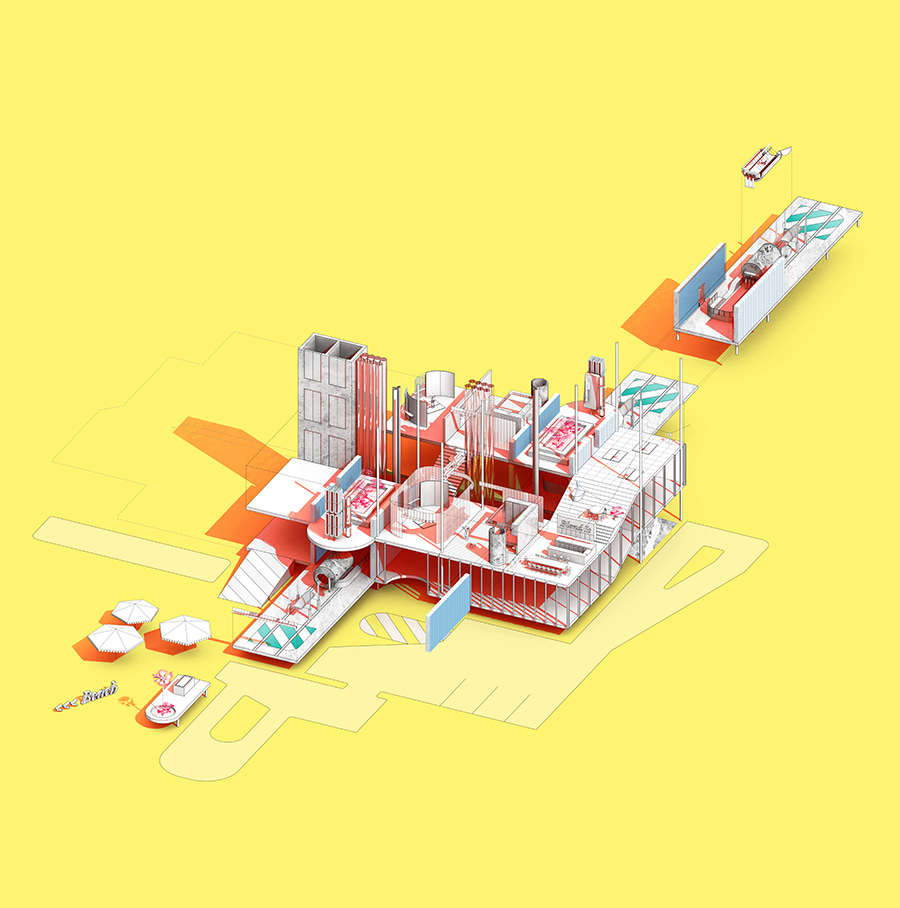

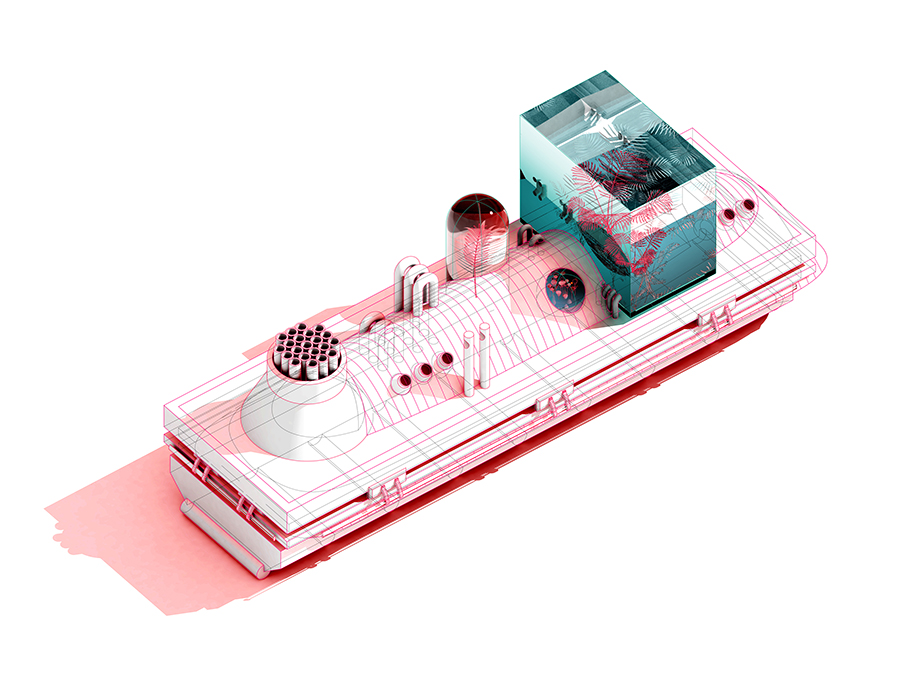

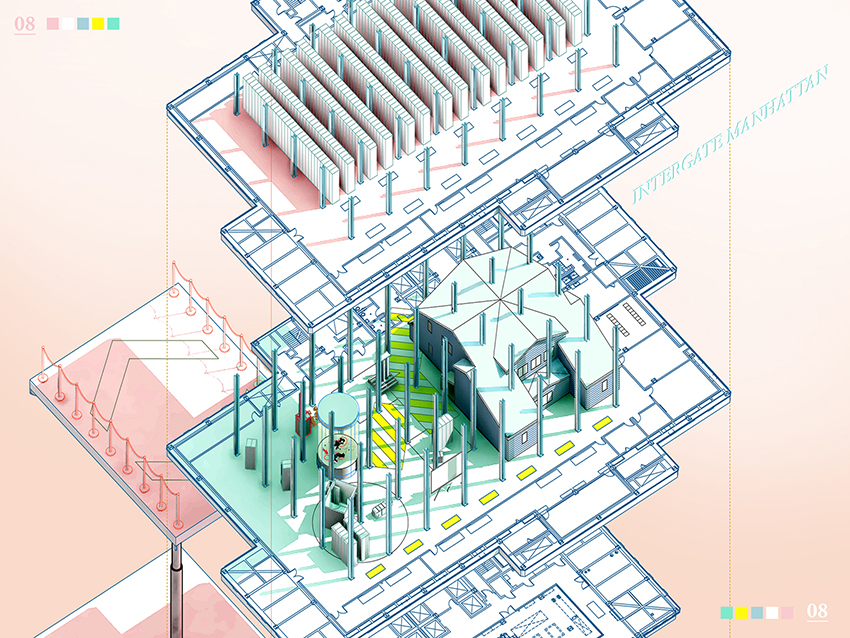

Closer Each Day speculates on the possibilities advanced by an embrace of the material business of death. The Closer Each Day: Protocols for Processing Drawing (the central representation in the project) describes new prototypes for housing anchored around the virtual afterlife and self-design; memorial gardens fertilized by anatomy-centered chemistry; ‘transfer cases’ that produce micro-ecologies and energetic outputs from human remains; and repositories for the leftover, personal effects of the urban dead. It describes several means by which logistics, informed by the US Military’s Department of Mortuary Affairs, can integrate the ceremonial with the infrastructural. In particular the process of alkaline hydrolysis takes priority in the project as a remains disposition method that liquifies the human body into a fertile solution capable of fostering the growth of memorial gardens and other plant life; the transfer of heat from its fluid effluence to other purposes; and even, as some have proposed, the biotic maintenance of some municipal infrastructure.

Beyond the identification of value, this project proposes opportunities for social engagement beyond biological expiration. In order to contextualize this work discursively, it is important to acknowledge that the last half-century of architectural discourse has contributed to the distancing of death from the urban, elaborating the metaphysical poetics of death as an island, apart from the everyday. Cemeteries and mausoleums proliferated amidst the stance that late modern and postmodern architecture took to its own history from the mid 1960s. Architects like Aldo Rossi, Enric Miralles, or John Hejduk, to name a few, explored the design of death with special attention to ritual, poetics, and aesthetics (perhaps also analogizing the corpse of high modernism), de-prioritizing its material and technological realities in favour of the metaphysical.

Closer Each Day: Protocols for Processing cites its discursive antecedents by adopting the colour scheme and long, hard-edged shadows of Aldo Rossi’s San Cataldo Cemetery images. Further, it acknowledges the augmented visibility that death might have in the urban realm by referencing the meandering, back-and-forth, organization of a drawing of the Duke of Wellington’s elaborate funeral procession as featured in the Illustrated London News from November 20th, 1852, led by the carriage designed by Gottfried Semper. The frame for the drawing includes a Jasmine scent diffuser called “Cozy Linen.” Unguentaria (commonly found teardrop vessels in hellenic graves as part of funeral rituals) contained Jasmine amongst one of the most common scents, which airscent.com lists as one of the most appropriate ambient smells for funeral homes if mixed with Metazene TM to neutralize the odor of embalming chemicals.